James Tipton 1812 - 1888

James Tipton was born on September 19, 1807, in Buncombe, North Carolina.[1] Around 1825, he married Mary Olive Rose, in Buncombe, North Carolina. Mary was born in July 1807.[2] By June 1, 1830, they had 2 girls under the age of 5.[3] And by 1849 they’d added 7 more children to their family: Jonathan in 1830, Charles and Susan in 1833, David in 1838, Sarah in 1843, and James J. and Harriet in 1849.[4]

The Tipton family did some moving around the country. Eventually like a lot of restless Americans at the time that journey took them west. By 1833 they had moved to Tennessee, and five years later in 1838 they’d moved to Virginia. Even five more years later they were in Ohio, eventually reaching Stark County, Illinois by October 1850. James was a farmer.[5]

James farmed in Illinois, until he decided to move his family once again, this time to Decatur County, Iowa. In 1856 he made two land purchases, one of 84 acres, and the other 40.[6] That same year records show of the land he bought, 35 acres were improved. He had 5 acres of Spring Wheat, and 30 acres of Corn. His corn yield was a little over 3 bushels per acre.[7] (According to records, a good to average corn yield was 30 to 50 bushels per acre. A ‘bad’ harvest was considered 4 to 8.) Records show that the Midwest and prairie states were experiencing a severe drought from around 1845 – 1856. This could be why the Tipton family moved so much, trying to move their way out of the drought. In 1856 the drought was accompanied by uncontrolled prairie fires, this probably accounts for James’ poor crop yield.[8] That year he also sold 2 hogs for $24, and 5 head of Cattle for $50.[9]

Luckily for James and his family their fortunes began to improve. In July 1860 his real estate was valued at $600, and his personal estate at $500.[10] Ten years later, in 1870, his real estate was $2,400, and his personal estate was $1,000.[11] It looked as if everything was going their way. But sadly, their youngest daughter Harriet died April 25, 1870, she was 21 years old.[12]

Sometime after August 1870[13], and June 1877[14], James and his wife Mary, moved to Whitman County, Washington. James took up his regular occupation of farming and started a Logging business.[15]

Before this area was settled by pioneers seeking new lands and opportunities, it was populated by several Indian tribes, the Coeur d’Alene, Spokane’s, Palouse’s, and the Nez Perce. As whites moved into native American lands, there were inevitable conflicts. As these conflicts escalated, the U.S. Army was called in to settle things. After some Palouse Indians raided and stole horses and cattle from several farms Lieutenant Colonel Edward Steptoe decided it would be a good opportunity for a show of force, to encourage the northern tribes to capitulate. On May 6, 1858, Steptoe took 160 soldiers, 3 Nez Perce scouts, and about 30 civilians to tend to the necessary pack train, to run down the miscreant Indians. They were under supplied for such a foray. Most soldiers carried inaccurate muzzle-loading muskets, which were very difficult to load while on horseback. Additionally, each man only carried 40 rounds each. They also hauled two mountain howitzers which proved totally useless.

On May 16, after camping the night before on the west side of Pine Creek they began encountering more and more Indians who had gathered to taunt them as they travelled through their territory. These Indians were armed and painted for war. The Indians soon stopped Steptoe’s column and demanded to know their intentions. Steptoe assured them his motives were peaceful, but the Indians did not believe him. The Indians blocked Steptoe’s troops and refused to let them pass. After careful consideration Steptoe decided that he would withdraw the next morning on May 17.

A peaceful withdrawal was not to be, setting out before dawn sporadic gun fire broke out on both sides, and after several soldiers were hit a full engagement commenced. The Indians almost split the troops, but they regrouped and circled up on a nearby ridge. After several unsuccessful charges the Indians chose to cease hostilities for the day. Steptoe after evaluating his situation, and almost out of ammunition decided a surreptitious retreat that night would be the best plan. He buried 7 dead troopers, and his two useless cannons and departed with no further losses.

A little less than six months later Colonel George Wright commanded a punitive expedition against the Spokane, Palouse, Coeur d’Alene, and Yakima Indian tribes. He was going to make them pay for what happened to Steptoe’s troops. “Colonel Wright came for blood.

On the arid plains of the Inland Northwest, he found it: sprayed across the battlefield at Four Lakes on Sept. 1, 1858, as his soldiers fired long-range guns into charging Indians. He found it again four days later: at the Battle of the Spokane Plains, where local tribes attempted to thwart U.S. troops by lighting fire to the dry grasses and were met with the thunder of Howitzers. The battlefield ran red with Indian blood.

“I did not come here to ask you to make peace; I came here to fight,” Wright told Chief Spokane Garry, chronicled in N.W. Durham’s 1912 “History of the City of Spokane and Spokane Country.” “Now when you are tired of war and ask for peace, I will tell you what you must do: You must come to me with your arms, with your women and children … and lay them at my feet. … If you do not do this, war will be made on you this year and next, and until your nation be exterminated.”

If threats of holocaust weren’t enough for local tribes to fear Wright, his subsequent acts surely struck terror into their souls. On Sept. 8, Wright’s men seized 800 horses from local tribes and began the sadistic process of murdering them on the shores of the Spokane River. For two days, the only sounds that could be heard were bullets, the crush of clubs against skulls, and high-pitched screams. “It was distressing …” wrote Lt. Lawrence Kip in his journal, “to hear the cries of the brood mares whose young had thus been taken from them.”

Wright then ordered the Indians’ barns of wheat and food destroyed, and cattle shot. This, Kip wrote, “will bring upon the Indians a winter of great suffering.” Two weeks later, on the shores of a sleepy creek buried in the Palouse hills, Wright lured Indian leaders under the ruse of a white flag. There he hanged Qualchan, a Yakama sub-chief accused of killing a white man, after a mere 15-minute interrogation. By the time Wright left Washington Territory, 16 more Indian necks would snap by his ropes.”[16]

When James Tipton arrived in Whitman County, Washington, there were still plenty of Indians around, but they mostly went about their own business. The ‘new’ settlers still viewed them with mistrust but overall had no real issues with them. Until June 14, 1877. That’s when Chief Joseph’s band of Nez Perce took up arms with local settlers in Camas Valley, Idaho. Many, mostly defenseless settlers, were killed before troops could arrive in the area to put down the uprising. Even though it was 420 miles away the citizens of Whitman County were concerned that the angry Nez Perce could be driven in their direction. Then rumors started to spread that local tribes were going to go on the war path and join the uprising in Idaho. More unfounded rumors spread of massacres by the Indians closer to home. In some cases, farms were deserted along with crops and livestock to escape the non-existent hostile Indians. In Palouse City, a 125-foot square blockhouse was built, housing 200 people for protection against the imaginary dangers. Others in town dug rifle pits on the hill sides. These actions caused local Indian tribes to become uneasy, these preparations appearing like they were for offensive not defensive purposes.

Seeing the growing panic in the local citizenry, twenty men organized themselves into a scouting party to determine if it was true hostile Indians were in the area. James Tipton was a member of this scouting party. They saw no traces of hostilities. None of the vacated farms had been disturbed, in fact local Indians in some cases had taken it upon themselves to feed the abandoned livestock of their absent neighbors. When the expedition reached Fort Howard, they learned that none of the Indians involved in the Idaho uprising were heading their way. They did hear a new rumor that a Catholic missionary was being held by the Coeur d’Alene. Two members of the expedition, D. S. Bowman, and James Tipton, set out to determine if there was any truth to the rumor. The rest of their party returned home.[17]

Bowman and Tipton found the Indians that supposedly had detained the missionary. The Indians were very excited, saying they believed that white settlers were preparing to attack them, so they were taking necessary precautions to protect themselves. Tipton and Bowman allayed the Indians fears, explaining the true situation and convincing them that no offensive action was being planned. Father Cataldo, the Catholic missionary provided affidavits from the Chiefs of the various tribes that they only had peaceful intentions. When Bowman and Tipton arrived back home, they reported what they had seen and handed over the documents provided by Father Cataldo. This went a long way to allaying the citizenry’s fears, and calming things down.[18]

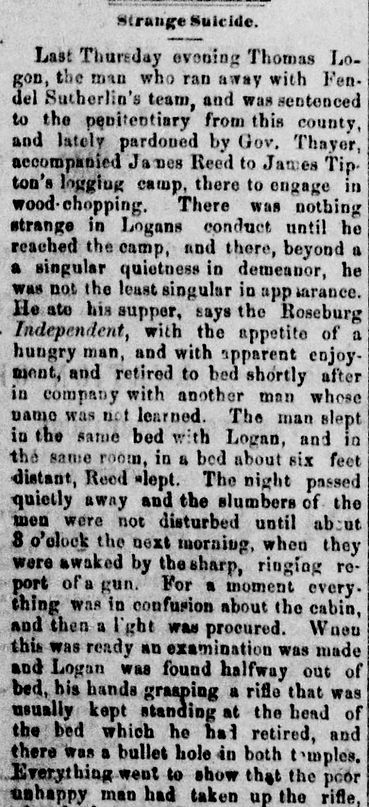

On August 28, 1879, James had some excitement at his logging camp.

[19]

On June 25, 1880, James was living on his farm with his wife Mary, son-in-law Frank Brown, daughter Elizabeth, and Grandson Thomas. According to the census Frank was a Farmer, and James showed that he had no occupation. James was still listed as head of household.[20] Sometime before James death he purchased some property about 45 miles away in Nez Perce County, Idaho. It’s unclear if he ever lived there, but after his death April 20, 1888, it was to be sold to settle his estate in Probate Court in Nez Perce County, Idaho.[21]

James was buried in Freeze Cemetery, in Freeze, Latah County, Idaho. Mary Olive, James’s wife, continued to live in Palouse, Whitman County, Washington, until her death on October 30, 1891. Mary was buried next to James in Freeze Cemetery, Freeze, Latah County, Idaho.[22]

[1] 1850 United States Federal Census & Tombstone

[2] 1850 United States Federal Census & Tombstone

[3] 1830 United States Federal Census

[4] 1850 United States Federal Census

[5] 1850 United States Federal Census

[6] Land Patent Certificates

[7] 1856 Iowa State Census

[8] Newspaper

[9] 1856 Iowa State Census

[10] 1860 United States Federal Census

[11] 1870 United States Federal Census

[12] Tombstone

[13] 1870 United States Federal Census

[14] Illustrated History of Whitman County State of Washington

[15] Lewiston Daily Teller, September 5, 1879

[16] The Spokesman-Review, May 17, 2015

[17] Northwind Picture Archives

[18] An Illustrated History of Whitman County, state of Washington

[19] Lewiston Daily Teller, September 5, 1879

[20] 1880 United States Federal Census

[21] Lewiston Daily Teller, September 20, 1888

[22] Find A Grave